A well preserved, lavishly decorated Byzantine church like the Chora can be read on severaldifferent levels. For the simple monk of Byzantine times or for the uninitiated tourist of today, its decoration presents illustrations from holy books – subjects occasionally familiar, occasionally obscure. On another level, the themes and subjects of the decorative program resonate with movements and verses of the Byzantine liturgy, and the art of the Chora can be understood as a reflection of the rituals that marked the daily life of a monastic church. On yet another level, the art of the Chora reflects the patronage of one of Byzantium‘s greatest intellectuals; it is as sophisticated and erudite as a work of contemporary Byzantine literature, structured like a vast epic poem.

The fourteenthcentury artists responsible for the decoration of Theodore Metochites‘ church began with the mosaics of the naos, then continued with the mosaic narrative programs and icons in the narthices, and concluded with the frescoes of the parekklesion. A trained eye can detect a stylistic progression in the paintings: they become more exuberant and mannered. The patron seems to have provided “hothouse conditions” for the painters to develop their personal styles, which mark a critical point in the history of Byzantine art.

The style of the painting has been eloquently described by Otto Demus, who noted that, at first glance, the art seems to have no acknowledged canons, as if the artists preferred the abnormal to the normal, the distorted to the regular, the chaotic to the harmonious. On closer scrutiny, however, it reveals a canon of taste no less well defined than sixteenthcentury Italian mannerism. Decorative motifs are used to join otherwise disparate elements, with much adjustment to fit irregular spaces. The architectural backdrops are like stage sets, replete with draperies, shrubbery, and incidental details. The tendency is toward the disintegration of the composition; equilibrium is unimportant and is replaced by asymmetry, instability, and unrest. Figures have oddly contorted postures and sometimes seem to fly through the air instead of being firmly attached to the ground; their draperies flutter in lively arabesques.

In part, the mannered artistic style came as a response to the architectural framework. The process of fitting the narrative scenes onto irregular surfaces lunettes, domical vaults, and pendentives – encouraged the distortion of the composition, perhaps most evident in the scenes from the Life of the Virgin in the inner narthex. At the same time, the artists were experimenting with compositions and figures. The compositions are based on an accumulation of details, understood on a small scale, and the whole is held together by a decorative veneer. Individual figures are seen in many unusual postures and from many different points of view, perhaps copied from sketchbooks, but each derived from a variety of sources.

In short, the Kariye Camii represents Byzantine art at its most experimental. In many ways, it offers a Byzantine version of postmodernism, in which the style is based both on quoting details from the past and on breaking the established rules in an attempt to create a new mode of expression. Its intellectualizing aesthetic would have appealed to connoisseurs like Theodore Metochites and his elite coterie. With the richness of the themes and imagery at the Kariye, one may easily overlook the style of the painting. But this was a critical element in the artistic expression, a part of the intellectual underpinnings that unify the building and its art.

Metochites explained the main purpose of the decoration of the church as relating “in mosaics and painting, how the Lord Himself… became a mortal man on our behalf.” Accordingly, the elaborate program focuses on interconnected themes of incarnation and Salvation. The surviving scenes include the Old Testament ancestors of Christ and Old Testament prefigurations of the Virgin foretelling the virgin birth – as well as cycles of the lives of Christ and of the Virgin, and the Last Judgment.

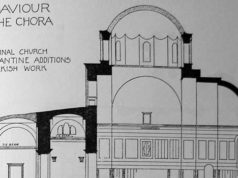

The naos preserves its fourteenthcentury marble revetments almost in their entirety but very little of its mosaics. The vaults and upper walls of the church were probably decorated with the most important scenes from the lives of Christ and the Virgin, the socalled Dodekaorton, or Twelve-Feast Cycle, as was standard in a Byzantine church, along with a bust of Christ in the dome and the Virgin enthroned in the apse. Of these, only the Koimesis, or Dormition of the Virgin, survives, along with standing figures of Christ and the Virgin on the piers to either side of the entrance to the bema. Because of the dual dedication of the church to the Virgin and Christ, the figures almost always appear as pendant images. The “gender symmetry” emphasized the role of the Virgin in the process of salvation. Moreover, the positioning of images within the architectural setting encourages a visual interplay that enhances their meaning. For example, the pose of the Virgin holding the infant Christ is mirrored in that of Christ, who holds the swaddled soul of the Virgin in the Koimesis: in one the Virgin appears as the vehicle by which Christ is brought to earth; in the other Christ appears as the vehicle by which the Virgin is carried to heaven. The two themes suggested by these images, incarnation and salvation, dominate the narrative programs of the church.

There are also numerous iconic images in the narthices as well. Many of these also reflect the dual dedication of the church and monastery. A bustlength image of Christ, labeled chora ton zoonton (dwelling place of the living), appears above the doorway leading from the outer narthex to the inner narthex. The facing image of the Virgin, labeled chora ton archoretou (container of the uncontamable), is depicted “containing” the Christ child in her womb. An oversized dedicatory image usually called the Deesis (prayer) appears in the enlarged southern bay of the inner narthex; it depicts Christ and the Virgin with the former founders Isaak Komnenos and the nun Melanie kneeling at their feet. Other framed images of standing saints decorate the pilasters of the narthices, and additional standing and bust-length images of saints decorate the arches. This “choir of saints” would also have provided points of focus for private devotion within the church. The terminal bays of the inner narthex are covered by domes crowned with bust images of Christ and the Virgin, surrounded by their Old Testament ancestors.

The lunettes and vaults of the narthices are decorated with cycles of the lives of the Virgin and of Christ. All begin at the northern end of their respective spaces, with thematic and visual references linking them. Three bays of the inner narthex are devoted to the story of the Virgin, from her miraculous birth to the elderly Joachim and Anna, to her childhood in the temple, her marriage to the elderly Joseph, and her miraculous pregnancy. The story is based on the Protoevangelium (or Apocryphal Gospel of Saint James), which was widely accepted during the Middle Ages. Unfortunately, the beginning of the cycle is broken by a structural crack in the north bay. Except for this damage, the inner narthex is one of the most satisfying spaces in the building, preserving its lavish original coverings on the floor, walls, and vaults.

The cycle of the Infancy of Christ is represented in the lunettes of the outer narthex, while its domical vaults are decorated with scenes of the ministry and miracles of Christ. Both cycles are based on the accounts in the Gospels and begin in the north bay. The Infancy Cycle commences with the Dream of Joseph, in which an angel assures him of the Virgin’s miraculous conception. This is followed by the Journey to Bethlehem and the exceptional episode of the Enrollment for Taxation, probably included because Theodore Metochites was the minister of the treasury and responsible for tax collection. The Nativity of Christ is set to parallel the Birth of the Virgin in the inner narthex. The stories of the Journey of the Magi, the Flight into Egypt, and the Massacre of the Innocents are then represented in multiple scenes. The cycle concludes with the Return of the Holy Family from Egypt and the youthful Christ being taken to Jerusalem.

The cycle of the Ministry and Miracles begins in the domical vault of the first bay of the outer narthex and concludes in the south bay of the inner narthex. The story proceeds directly from the conclusion of the previous narrative, with Christ in the Temple of Jerusalem, now almost entirely lost. As with scenes in the inner narthex, the narratives are sometimes stretched and contorted to fit into the domical vaults. Usually, two different episodes appear in each vault. Several areas of mosaic are missing in this cycle, but almost all of the scenes can be identified, including John the Baptist proclaiming Christ and the Temptation of Christ. The other vaults are filled with numerous scenes of Christ’s preaching and healing miracles.

In a like manner, the diagonal angles of the sarcophagi of Adam and Eve in the Anastasis lead the eye toward the tomb arcosolia along the lateral walls, just as the unique domical composition of the Last Judgment envelops them – as if the tombs have become part of the composition. Artistically, the parekklesion may be best understood not so much as a fresco program set into an architectural space as an architectural space that has become an integral part of its decoration.

Throughout the building, Old Testament and New Testament themes are related: the prefigurations of the Virgin in the parekklesion – as the Ark of the Covenant, the Burning Bush, or a walled city – hark back to the images of containers and to the theme of the Virgin as the “container of the uncontainable” in the outer narthex. Similarly, a visual mimesis associates various images and themes. For example, the positions of Adam and Eve raised by Christ in the Anastasis fresco recall the proskynesis of the angels flanking the Virgin in the dedicatory image above the main entrance in the outer narthex: the ultimate image of salvation recalls the premiere image of the Incarnation. In a like manner, the flowing red robe of Eve in the Anastasis mimics the form of the fiery stream of hell in the Last Judgment, subtly calling to mind simultaneously the fall of man and his ultimate salvation – and adding nuance to the gender symmetry of the program.

Minor details also encourage more complex readings: for example, David of Thessaloniki, a dendrite (that is, a hermit who sat in a tree) shown at the entrance to the parekklesion, is positioned equidistant between Christ Calling Zaccheus (who had climbed a tree in order to see Christ as he passed through Jericho) and Moses before the Burning Bush. In each, we witness an encounter with the divine – Old Testament, New Testament, Byzantine. Even the inscriptions enhance the visual expression of the images: for example, the drama and violence in the Soldier Pursuing Elisabeth with the Infant John the Baptist (the last scene in the cycle of the Massacre of the Innocents) is emphasized by the soldier’s sword severing Elisabeth’s name in the inscription: ELI//SABETH. In sum, both in style and iconography, the Kariye Camn is a masterwork, its mosaics and frescoes creatively coordinated within a complex architectural setting.

The Wedding at Cana and the Multiplication of Loaves are taken out of their proper chronological sequence to be placed on the central axis of the outer narthex, with images of vessels of wine and baskets of bread dominating the scenes. Containers with the Eucharist are set before the image of the Virgin as “container of the uncontainable” and thus mark the beginning of a liturgical axis that led to the altar, where the communion was administered. Similarly, in the inner narthex, the scenes associated with the temple (represented as the sanctuary of a Byzantine church) are clustered on the main axis leading to the sanctuary.

Like the program of the narthices, the program of the parekklesion is divided between the Virgin and Christ. Here, however, the overriding theme is salvation, as befits a funeral chapel. Arched tombs, or arcosolia, line the walls of the chapel, which is decorated with fresco, rather than mosaic and marble revetments. The lower walls are painted to resemble marble paneling, forming a dado, and the walls are filled with standing figures of saints. The western domed bay is devoted to the Virgin; the upper walls in this area represent Old Testament prefigurations of the Virgin, emphasizing her role in salvation. The scenes and inscribed verses are drawn from the special readings for the feast days of the Virgin. She appears in the dome, surrounded by a heavenly host of angels. In contrast, the eastern bay is devoted to the Last Judgment, flanked by the punishments of the damned and the entry of the elect into paradise. The complex program of the chapel culminates in the conch of the apse, where the Anastasis (Harrowing of Hell) is represented: Christ, clad magnificently in white, having broken down the gates of hell, raises Adam and Eve from their sarcophagi, with Satan bound and gagged at his feet. To either side are scenes in which Christ raises a man and a woman from the dead.

The program of the parekklesion establishes evocative links between past (Old and New Testament scenes), present (the deceased in their tombs), and future (the end of time represented by the Last Judgment), offering assurances of salvation for those interred here. For example, the tomb of Theodore Metochites is set beneath the main dome, in which the Virgin is represented as Queen of Heaven. On the wall immediately above his tomb is the scene of Jacob’s Ladder, while in the pendentive above it the hymnographer Theophanes is shown composing a funeral ode on the subject of Jacob’s Ladder as a guarantee of access to heaven. Theophanes pauses, pointing his pen toward the tomb of Metochites. Similarly, in the Last Judgment, Christ gestures toward an image of a soul (usually interpreted as that of Theodore Metochites) presented for judgment by Saint Michael, and toward the tomb of Metochites himself.