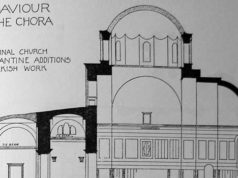

Complexity appears more important than monumentality in the architecture of the Kariye, and in the hierarchy of function each unit is clearly defined visually. The architecture parallels the elegantly mannered style of the art it houses, full of figures with strange postures and different views connected by a decorative veneer, the extended evocative narratives, and the obscure allusions – all part of the artful breaking of established rules. Even the marble revetments betray a restless mannerism. In the inner narthex, the repeated patterns consciously avoid the architectural divisions: the framing bands never occur at the pilasters but instead provide a visual counter point to the architectural framework. Similarly, along the south facade, the rhythm of pilasters is quickened, with pilasters and halfcolumns illogically positioned to “support” the windows. Details such as these are odd, to say the least.

These stylistic traits may be associated with the patronage of Theodore Metochites, who as an author was selfconscious about his own originality. Significant parallels to the art of the Chora can be found in his mannered and obsessive literary style. Like his writings, the complex style of the Chora can be understood as an expression of the personality of Metochites the intellectual. The intricacies and subtleties would have been missed by the average visitor, but they would have been appreciated by Metochites’ coterie of aristocratic intellectuals. In fact, they may have been intended to distinguish the true intellectual from the common rabble. Like postmodernism, the style of the Chora had snob appeal.

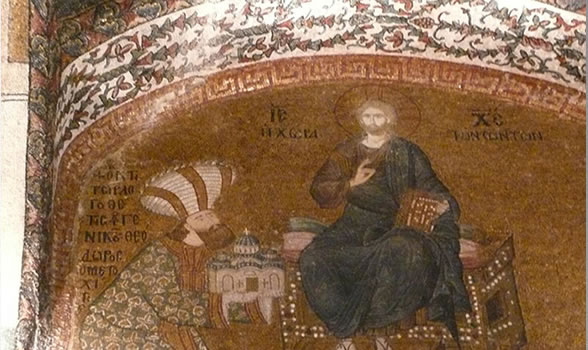

Theodore Metochites was fortunate to find a master mason and painter who were, in artistic terms at least, his equal. The clever artist responsible for the decorative program responded to the restless intellect and the ego of the patron. Through the careful manipulation of the architectural space and the painted program, he subtly draws attention to the benefactor: from certain vantage points, the viewer is positioned to pay homage to Theodore Metochites. In the parekklesion, for example, the viewer who pauses to admire the panoramic sweep of the decoration stops directly in front of the founder’s tomb. The gestures and lines within the fresco compositions also lead ultimately to the tomb of Metochites. Yet, in spite of his ambition and his many accomplishments, Theodore Metochites proved to be all too mortal. He was selfcentered, anxious, and sensitive. He was proud of his hardwon culture and status, which in his mind were inextricably connected. Metochites’ life was unhappy, in many ways a failure. He was rich, but at the expense of the poor. He achieved great stature only to fall dramatically from power in the palace coup of 1328. Despised by his contemporaries, ousted from office, and stripped of his worldly wealth, he died a simple monk. As the noted Byzantinist Ihor Ševcenko insists, Metochites nevertheless deserves our admiration: “To have given us the Chora he had to be a man of wealth, taste, and intelligence. He did not have to be a perfect gentleman.”