The dramatic mosaics and frescoes of Istanbul’s Kariye Camii, or Church of the Chora, blew away the stiff conventions of Byzantine art. Their energy leaves Giotto looking staid. But theyare now in danger of turning to dust. The powerful pictures on these pages are from a new book by Robert Ousterhout, who fell in love with the church twenty-five years ago. Here he makes a passionate case for preserving this fourteenth-century masterpiece

When I first set foot in the Kariye Camii years ago, I fell in love. It was the academic equivalent of a blind date – I’d committed myself, sight unseen, to write a PhD dissertation about a building I’d never seen in a city I’d never visited. Happily, the Kariye caught and held my interest.

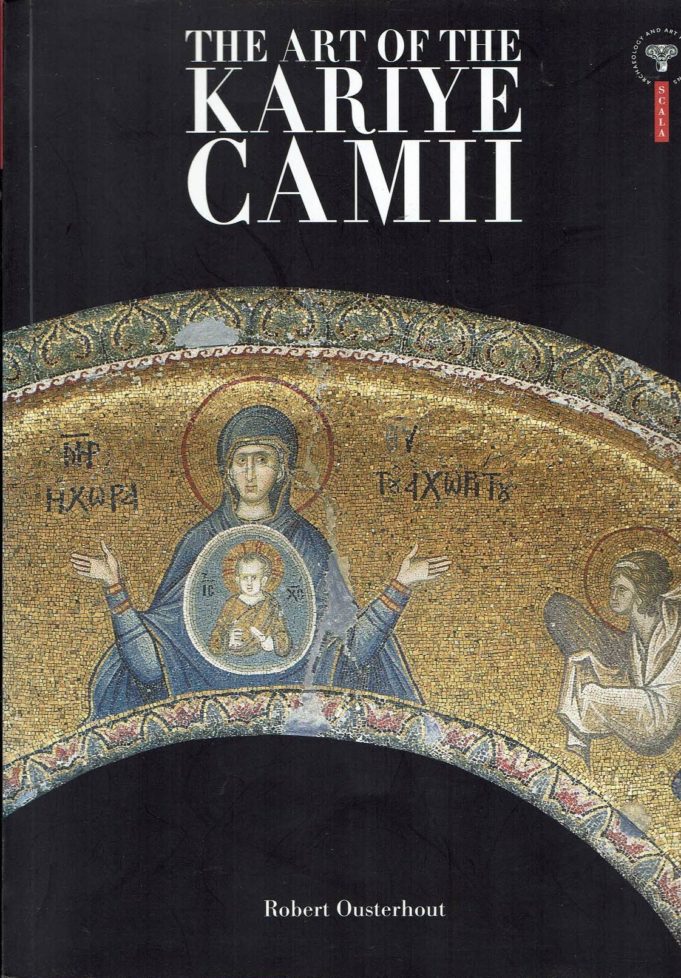

In fact, the Kariye proved to be the perfect blind date, possessing both beauty and brains. As I quickly discovered, the dazzling spectacle of its mosaics and frescoes was balanced by a coherent architectural framework and by firm intellectual underpinnings. It is one of Istanbul’s greatest treasures, once the main church of the Byzantine monastery of the Chora, and now a well-visited museum. Built and decorated between 1316 and 1321, the Kariye represents the patronage of Theodore Metochites, one of Byzantium’s greatest intellectuals, who was both an accomplished poet and prime minister. As sophisticated and erudite as a contemporary work of Byzantine literature, the Kariye is structured like a vast epic poem.

Theodore Metochites, famously depicted above the entrance in his big hat, was not only a powerful politician and the greatest scholar of his age, but he was also fabulously wealthy – the ideal patron for a project like the Kariye. More importantly, he was fortunate to find artists capable of translating his vision into built form. The hothouse conditions Metochites provided led to one of the most experimental periods of Byzantine art. If the word originality can be applied to the Byzantine, the Kariye is as original as it gets.

As the art historian Otto Demus once commented, at first glance the art of the Kariye seems to have no acknowledged canons, as if the artists preferred the abnormal to the normal, the distorted to the regular, the chaotic to the harmonious. It is the Byzantine equivalent of Postmodernism, breaking all the rules, but doing so in such a delightful way that we barely notice. As the key monument of late Byzantine art and architecture, there is absolutely nothing that can compare with it in Istanbul, or anywhere else for that matter.

Ten years after my first encounter, I was still in love with the Kariye. Our relationship had survived the dissertation, the revisions and, finally, the publication of the monograph. Then, after twenty-five years, I celebrated our silver anniversary with the publication of a second book. Although I began with a study of bricks and mortar, I found I couldn’t ignore the mosaics and frescoes. To be sure, I have been involved in a variety of other projects, but I keep coming back to the Kariye.

With its intricate architectural settings and its wealth of decoration, with each visit I seem to discover something new. On my last, for example, I started noticing the trees, how and where they are represented: in addition to a variety of expressive stumps and shrubbery in the mosaics, I realised that David of Thessaloniki, a dendrite (that is, a hermit who sat in a tree) shown at the entrance to the funeral chapel, is positioned equidistant from Christ Calling Zaccheus (who had climbed a tree in order to see Christ as he passed through Jericho) and Moses Before the Burning Bush. In each, we witness an encounter with the divine – Old Testament, New Testament, Byzantine.

Byzantine poets loved this kind of comparison. On an earlier visit, a friend pointed out how the drama and violence in the mosaic of the soldier pursuing Elizabeth with the infant John the Baptist (the last scene in the cycle of the Massacre of the Innocents) is emphasised by the soldier’s sword severing Elizabeth’s name in the inscription: eli-sabeth. Words and images work together.

Guidebooks are quick to point out the contemporaneity of the Kariye with the work of Giotto – as if we needed the Italian Renaissance to appreciate Byzantine art. There is certainly a similar power and sense of life in both, but the Byzantine artist worked differently from his Italian counterpart. Giotto developed an early system of perspective, so that his scenes appear as if viewed through a window, in a space beyond the picture plane. In contrast, for the Byzantine artist, pictorial space and the space occupied by the viewer were one and the same. As a consequence, the scenes at the Kariye have a greater sense of immediacy and are thus more emotionally compelling.

What is more, the setting for the art is not the flat walls of a big anonymous box (the typical Italian church), but rather a series of small, tightly interlocking spaces, in which architectural form and decoration are perfectly fitted together. We are led – personally, experientially – from one space to the next by the narrative, by the gestures of the figures and by the visual and thematic connections between the scenes.

The Byzantine artist did not attempt to create an artificial space through the science of perspective; instead, he created three-dimensional representations that come to life as we interact with them. Where else can we walk through the midst of the Last Judgment, with the scroll of heaven rolled up above our heads, flanked by the blessed and the damned?

The Kariye owes its preservation to the vagaries of history. It is set in what was originally a rural area by the land walls – the name Chora may be translated as “in the fields” – in the northern corner of the city, which became a hub of activity in the late Byzantine period, with the nearby Blachernae Palace as the main imperial residence. After the Ottoman conquest in 1453, however, the centre shifted back to the end of the peninsula, to Topkapi Palace, and the Chora church became an all-but-forgotten neighbourhood mosque.

Through the early Ottoman centuries, its decoration remained uncovered and, in fact, was never completely covered. The frescoes were whitewashed, some of the lower mosaics were removed, but the dome mosaics remained visible, and some of the wall panels were covered with wooden doors – to be opened to visitors for a small tip. When the Byzantine Institute of America undertook its extensive programme of cleaning and consolidation between 1948 and 1960, the surviving mosaics and frescoes were discovered to be in pristine condition.

Not so today. Both the Kariye and I are older than when we first met. The rapid growth of Istanbul’s population has increased the levels of humidity and pollution throughout the city. Crowds of visitors have also raised the level of humidity inside the building, which may be compounded by the lush garden planted close to its foundations, as well as by leaks in the roof and windows. The results are all too visible: in the parekklesion (the funeral chapel) the painted plaster has crumbled away at floor level, and efflorescence, or “bloom” (dampness causing salts to leach through the plaster and collect as a cloudy white substance on the surface), now obscures many painted scenes. For example, Theophanes the Hymnographer is represented below the dome in the parekklesion. He pauses while writing a funeral ode on the theme of Jacob’s Ladder as a guarantee of our access to heaven, holding his pen to point towards the adjacent scene of Jacob’s Ladder and, beneath it, the tomb of Theodore Metochites.

His meaningful gesture, which served visually to connect these several elements of the composition, is now all but invisible. A similar cloud of bloom obscures the Daughter of Jairus, raised from the dead by the hand of Christ, as well as the figure of Satan bound and gagged in the great fresco of the Anastasis (the Resurrection) which forms the visual termination of the parekklesion. Within the mosaics, protective covers of Perspex have created micro-environments in which the humidity is concentrated, causing the setting plaster to crumble.

What is to be done? First, a careful evaluation of the building, its mosaics and frescoes, is required, followed by a comprehensive programme of conservation, regular monitoring, and possibly the installation of climate controls. In France, the Lascaux caves, with their famous prehistoric paintings, have been closed to tourism and the interior environment sealed, controlled and carefully monitored. Even the scientists are allowed only limited access. It may be that nothing quite so drastic is required at the Kariye, but as a new government is elected, it might be worth reminding it that the long-term preservation of Turkey’s unique cultural heritage deserves greater priority than the quick-fix economics of tourism.

As I escorted a friend’s aged grandmother through the Kariye recently, it occurred to me that old buildings are like grandparents.

We love them just as much in their old age. But they require periodic check-ups and regular care – and occasionally treatment by specialists and prescription medicines. I am still in love with the Kariye Camii, but right now it needs urgent medical attention.

by Robert Ousterhout, author of The Art of the Kariye Camii

Article with historic photgraphs published in Cornucopia 27